I started taking a drawing class a few weeks ago. I’ve taken art history classes before, but I’ve never had formal art or design training — I’ve only ever been in writing and filmmaking courses.

So in many ways, I’m completely at sea in this drawing class. I have absolutely NO IDEA what I’m doing, and that is such a weird feeling. My hands actually shook a bit with nervousness on the first day as the instructor basically threw us into a bunch of visual memory and observation exercises without a ton of explanation. I felt that weird tightening in my chest that is basically “OH MY GOD I AM GOING TO BE SO SUCKY AND I HAVE NO TALENT AND EVERYONE WILL LAUGH BECAUSE I AM THE LAMEST.” And it’s true: I feel a lot slower than others in my class, dome of whom have clearly already been drawing since forever. I was drawing a little figurine and I only managed to finish the top of it when we had to move to the next exercise!

But I kind of got over my initial feelings of potential loserdom, fear of judgment and embarrassment — which I recognize will always plague me whenever I take any kind of risk. Perhaps it’s leftover pressure from my days as a former high-achievement junkie, or just part of my nature to want to do my best all the time. I’ve spent a lot of my adulthood feeling competent in one way or another, so it’s really strange to just be so at sea.

But the truth is, it is nice to be really new at something, to just leap and have no goals and just explore and find pleasure in something. Almost every creative endeavor and project in my life is goal-oriented and structured in some way. While that’s important and good — especially when you take something very seriously and want to succeed in it — it’s nice to have something where play is paramount and there’s no pressure except just to enjoy learning it.

You always hear talk about “beginner’s mind,” which is a very Zen concept that involves approaching something in a fresh and clear way without prior assumptions or burdens. But for me, the real pleasure of beginner’s mind is bringing a renewing sense of playfulness to an endeavor. It’s nice to be an auntie to young children, because my niece and nephews are forever playing. Playing for them isn’t about publishing a story or getting into an exhibition: it is having fun in the process, having no inhibitions or rules and just making it up as you go. It isn’t about wrong or right: it’s about joy and pleasure and moments — and sometimes just being goofy and silly and willing to look ridiculous. Ridiculousness is actually a huge element when I play with my nieces and nephews — the more we can flout the accepted way of doing and being, the better and more amusing of a time we have together.

Sometimes it’s nice to infuse this sense of play back into something you’ve been doing a long time. For me, that’s writing: it’s something I’ve been doing for ages, I studied it as a creative discipline and I do it for my job. One of my life goals is to achieve mastery, a kind of alchemy of skill, vision, conviction and confidence. But oddly enough, I’m finding that mastery is about keeping things fresh and even fun, putting myself back into a position of newness and uncertainty. Sometimes this means trying to write a story from an entire different perspective, or writing it backwards, or writing a poem instead of fiction. Sometimes it means attempting a new genre or form. Or it means writing something you never ever thought you’d write. Sometimes I’ll even write by hand — or write with my non-dominant hand. The trick is to challenge your entrenched assumptions and habits, whether they’re emotional, imaginative or technical. (I suppose this applies to not just art and creativity but life as well; it’s certainly a bit of a trick to contemplate changing up a long-established relationship to create newness and playfulness.)

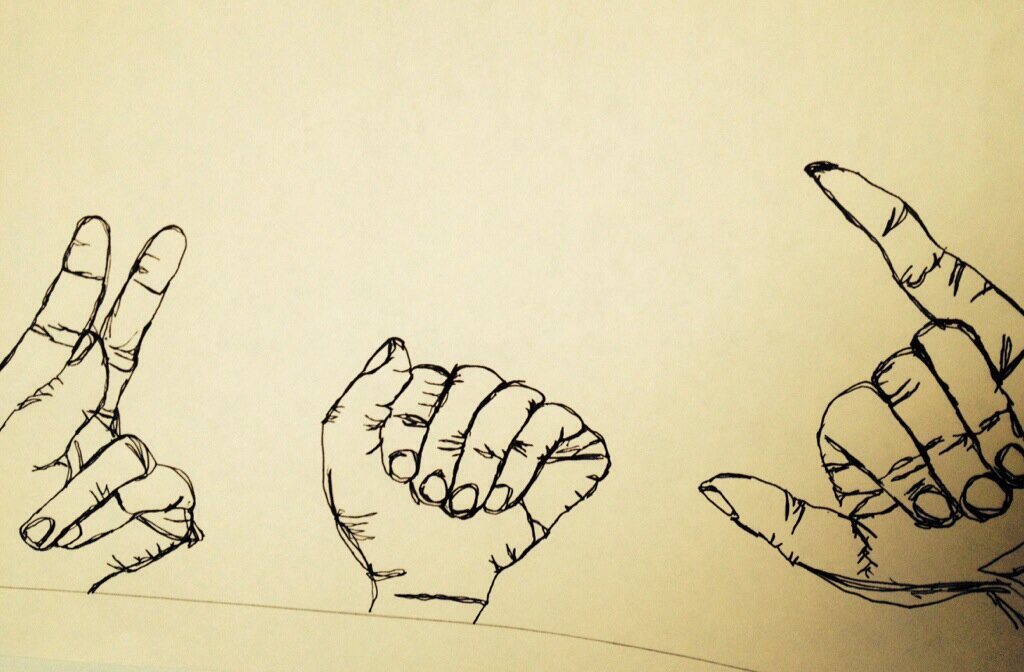

Or, you can just try something completely and utterly new, which is the route I’ve taken this spring with this drawing class. I don’t ever see myself becoming a great visual artist in any way, nor do I want to. But it is kind of just fun, and fun is so underrated as a guiding virtue in life. Just this past week we learned line contouring drawings and one of the warmup exercises was drawing “blind” — we drew our hands with marker pen, only we didn’t get to look at our paper as we drew, and we could only use one continuous line, so our markers couldn’t leave the paper. The objective wasn’t to produce a great drawing, but to slow down and really look at something. Of course, the results were crazy-looking and hilariously Gollum-like. But once I relaxed into it and just enjoyed the process of trying something totally new, it didn’t matter. It was fun, it was new and it felt fresh and true.